The Physics Engine – Introduction

This story was drawn for a wonderful New Zealand book, Are Angels OK? The Parallel Universes of New Zealand Writers and Scientists, edited by Paul Callaghan and Bill Manhire, and published in 2006 by Victoria University Press.

This story was drawn for a wonderful New Zealand book, Are Angels OK? The Parallel Universes of New Zealand Writers and Scientists, edited by Paul Callaghan and Bill Manhire, and published in 2006 by Victoria University Press.

Are Angels OK? was a project put together by Paul and Bill to mark the World Year of Physics in 2005 (which was the centenary of Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity, in case you’re wondering). The basic idea was to get a bunch of NZ writers to sit down with NZ physicists and just talk about whatever took their fancy. The nature of these conversations was totally undefined; the one requirement was that each writer would then produce a new piece of work, to be collected in the book.

I was assigned three physicists from the University of Auckland, two of whom I ended up having some totally mind-blowing discussions with: Professor Geoff Austin (who among other things is an expert on the physics of clouds) and Associate-Professor Matthew Collett (who, in addition to experimenting with light teleportation, is an active Catholic and a tabletop wargamer). I also read a heap of books on relativity, quantum physics and the relationship between science and art. For the better part of a year, I was thoroughly immersed in physics – a subject I’ve always had a passing interest in, but never had a reason to study more closely.

Along the way, a strange thing happened. At first, I thought I’d do a story about clouds, making use of Professor Austin’s expertise in the field, and tying it all to Atlas, which partly revolves around the notion of trying to map the sky. And we did talk about this for a while – and I wrote copious notes on the subject. Geoff was a very cool guy to talk to – a scientist who once worked for NASA, flies bi-planes, has travelled all over the world and even has one of those groovy radar vans that storm-chasers park in the path of tornadoes and cyclones. But the two things that really stayed with me, and ended up affecting my world view even more deeply than the weirdness of relativity, were Geoff’s offhand remark that he loathed the fantasy genre (on account of its total disregard for the laws of physics) and the time we went to the art gallery together.

The art gallery visit was Geoff’s idea. Turns out he also paints in his spare time (no doubt a lot better than I do!), and he’s always been interested in the way artists depict clouds and skyscapes. As a physicist with a deep understanding of the inner processes that shape cumulonimbus clouds, he can’t help but assess the accuracy of a painted rainstorm. It just so happened the Auckland City Art Gallery was hosting an exhibition of landscapes by William Hodges (a British artist who accompanied Captain Cook on his first voyage to New Zealand), including one of Geoff’s favourites, a dramatic painting of a waterspout off Cape Stephens. As we walked around the gallery together, I listened to Geoff talking about why this or that skyscape was credible or not, which clouds could never have existed in reality, and which were clearly sketched from life. And I knew there and then I would never have the courage to show him my own drawings of the sky…

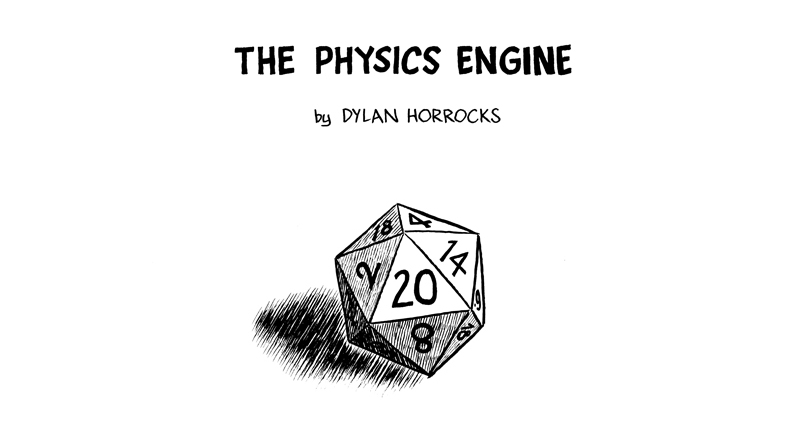

Meanwhile, my one long, indepth conversation with Professor Collett ranged all over the bizarre interface of quantum and classical physics, the apparent magic of quantum entanglement and simultaneity, and more. But, again, it was unexpected details that stuck in my head: our brief discussion about the role of dice in wargames, and Professor Collett’s apparently genuine Christian faith. The latter set me off on a long exploration of the relationship between science and religion, which in turn got me thinking about the way art has replaced religion for many people, as a means to give ‘meaning’ and ‘meta-narrative’ to the world.

All this coincided with one of the darkest periods of my life as a cartoonist – a time when I had lost faith in stories and art and could no longer enjoy either. In a sense, I suppose I was having a spiritual crisis – a funny feeling for a lifelong atheist. But like I say, in these secular times, many people fill the hole with art – a strategy that simply wasn’t working for me any more. A significant moment came when I took a book about UFOs out of the library (as light relief from all the heavy science I was reading). And buried in there was a line that summed a lot of things up for me. The author (a religious studies scholar) quoted a journal article on the subject of pseudoscience and the motives of those who promote it:

Their work… might be interpreted as efforts to re-enchant the world through science. They would bring back into science’s ken the monsters, giants, wee people, dread cataclysms… that once upon a time were exorcised from science and by science. There is, in other words, a fascinating apparent effort to be “for” science and yet, at the same time, against its “impoverishing” impact on our modern world view.

Lyell Henry, quoted in Brenda Dazler, The Lure of the Edge: Scientific Passions, Religious Beliefs and the Pursuit of UFOs.

That phrase “…to re-enchant the world” went off in my head like a supernova. That’s what art tries to do, I thought – or at least, that’s what I’d been using art to do, before my crisis of faith. I’ve always been obsessed with fantasy and magic – always looking for another novel that would have the same effect on me that Tolkien had when I was 12; spending years of my life immersed in fantasy role-playing games, in search of that spine-tingling feeling of really being in another world, another reality… Even so-called ‘literary fiction’ is trying to create an alternative version of reality, one in which everything is saturated with meaning, with significance, with beauty or power.

Unfortunately, I’d lost the ability to suspend my disbelief. I no longer believed in enchantment; the world has no meta-narrative, no meaning, no innate beauty or magic. There’s only the myths we tell ourselves in an effort to make it seem as though such things really exist. As Nietzsche grimly put it: “Truth is ugly. We possess art lest we perish of the truth.”

Ouch!

Anyway, by now, all thought of a nice story exploring the physics of clouds was long gone. I needed to do a story about art and fantasy, science and reality. And so I went back to the moments in my discussions with Professors Austin and Collett that haunted me most: Geoff’s rejection of fantasy and his critical analysis of William Hodge’s clouds; Professor Collett’s religous faith and our shared interest in simulation games. And somehow, I ended up doing a comic about D&D…

March 3rd, 2009 at 5:57 pm

Firstly, welcome back! Loss of faith for an artist is like a constantly aching ‘phantom limb’… an emptiness that insists on constantly reminding you what’s missing in a painful way. I’m so glad to see you in fine form, and absolutely love this story and the idea of ‘real’ fantasy.

On a personal and related note, my whole intention with The Secret Saturdays was to expose kids to the glamour of pseudoscience, to reacquaint the public with the notion that undefined, unproven, and undiscovered science is nothing less than magic. The same room with the lights out.

March 4th, 2009 at 11:17 am

Hey Jay – thanks! That whole loss of faith thing will be a big part of Sam Zabel & the Magic Pen, too. In fact, writing that story began partly as a way of making sense of it all.

That totally makes sense about The Secret Saturdays. I LOVE all that stuff, and another reason that quote about pseudoscience resonated for me was that it clarified why. Of course, the border between “pseudo” and “legitimate” science can be vague at best… 😉

The funny thing about this story is that I wrote it in a fit of despair about art and fantasy – but in the end, after drawing it, I kept looking at that final page and – well, it began to change how I felt about it all. I think I’d accidentally led myself to a new appreciation of why I do this stuff…

Anyway, back to work!

March 8th, 2009 at 6:38 pm

this is wonderful.

March 9th, 2009 at 7:19 pm

I’m always left wondering why you don’t forget your roleplaying film idea and do it as a comic (and then I think about how much work it would be (and the law suits)) – but everytime I read this story I am left thinking about it.

January 5th, 2010 at 12:23 pm

Is there anything worse for an artist than to lose their sense of wonder? I only ask because I am facing a similar disillusionment in my abilities as a cartoonist. I struggle constantly with societal obligations to be “successful” (i.e. maintain a particular financial solvency, since money appears to be the root of legitimacy in this existence) and a desire to involve myself fully with a reality I only have access to if I draw or write it. I allow too many distractions (some necessary, others not so much) to keep me from achieving the level of artistry I aspire to and continually second guess that any project I work on will garner any attention from financiers who will prove that these dreams are legitimate and not a waste of time. I suppose what I’m trying to say in a not very succinct way is; for someone with terrible insecurities like myself I find it difficult to push through all the nay-saying criticisms and modern distractions in order to just enjoy the actual practice of art. There was a time when simply putting a pencil on paper and making a representation thrilled me, but now I wonder whether or not anything I might scribble (which will probably never equal anything close to the level of draftsmanship I observe in the artists I admire, you being one of those) will be of interest to anyone? Do you, who it seems has conquered this malady, have any words of encouragement for a artist down and out at the boards? I understand you may be busy so please do not feel burdened to respond. I only inquire because you maintain a level of unabashed intimacy with your process and am hoping that I might gain some insight into how such a thing can be achieved. Thanks for all the wonderful work you’ve shared with your stories and I hope you continue to enjoy producing them. I also apologize for the potentially maudlin tone of this diatribe.

January 15th, 2010 at 2:30 pm

Hey Ryan – your stuff is lovely! You’re a much more proficient and natural draughtsman than I’ll ever be – and your brush line is gorgeous.

As for the mailaise, I don’t know if I have any very good advice. But it’s wonderfully liberating when you can sidestep all of those concerns and just write and draw for the pleasure of it – without worrying about whether anyone else cares. The trick is how to do that…

One thing is that I think we tend to fret about our drawing much more than we need to. There are two things I often remind myself:

1) drawing isn’t simply a matter of transfering what’s in my head onto the page. It’s really a collaboration between my mind, my hand, the pencil/pen and the paper. All of those partners in the process have something to contribute, and whether you like it or not, they will force their way in and have their say. So whenever I draw something, I know that I won’t get precisely what I set out to make; but hopefully I’ll be pleasantly surprised by what comes out…

2) When I give myself a hard time about my drawings, what I’m usually doing is feeling bad because they don’t look like someone else’s drawings (Blutch, or David B, or Craig Thompson, or whoever). Which is silly, because no-one can really draw quite like anyone else. I’ve decided drawing is like handwriting – it’s very personal and physical and gestural. I can only draw like me – but then, the flipside is that no-one else can draw quite like me. Even Blutch can’t do that…

So I’ve learned to accept the way I draw, as something like my own unique voice. I can work on improving and polishing that voice, but I can’t simply replace it with someone else’s, or with one that’s cleaner or higher or always hits the right notes. Instead, I concentrate on using it as powerfully and honestly and expressively as I can…

I doubt any of that helps, but hopefully you’ll find your own way back to loving your work – after all, it looks great to me!

December 19th, 2010 at 2:01 pm

[…] From The Physics Engine […]